“It reads like a summary of the year so far: drought in Europe, floods in Pakistan, and a high-pressure system ‘stuck’ in the North Atlantic, disrupting normal weather patterns. And scientists blaming it all on climate change.” It is not a quote from a recent article in The Guardian, but it dates back to 1978.

“The climate crisis? The Guardian has been investigating it for more than 100 years” by Mark Rice-Oxley and Richard Nelsson, is an interesting article published in The Guardian on 02 October 2022. It highlights how the Guardian and Observer journalists have been writing and publishing articles on climate events and warnings for a hundred years.

Just an example: “The Gulf Stream has changed its course… This change, we are told, has been in operation for two years, and as a consequence, New England has almost forgotten the rigours of winter.” It was reported on 25 January 1890.

Since 1997 after the Kyoto agreement, “The Guardian” has increased its attention to the climate issue. By 2009 the British newspaper hired “climate” reporters and declare the climate issue an editorial priority. In 2019 The Guardian’s Environmental Pledge: “We believe, it’s time to act”, and “We want to play a leading role in reporting on the environmental catastrophe.”, reads Guardian’s pledge, defining a precise and committed editorial line.

There is no doubt that this example is a best practice that other newspapers should follow and further develop. However, it could be the case that other newspapers have a history of climate journalism, albeit less known and perhaps not adequately structured and embedded in a specific editorial policy.

Is neutrality of communication an issue?

The stance taken on the climate and environmental crisis not only by “The Guardian”, but also by the magazine New Scientist and the BBC, opened a debate on the role of journalism in supporting and popularising the climate culture.

More precisely, questions emerged on the neutrality of journalism, or whether communication in any form is neutral.

However, does it make sense to speak of neutrality in journalism and communication? How to do it in practice? Publishing articles that openly take a stand on climate change alongside others that deny it or are sceptical about the responsibility of human activities in climate change? Neutrality could be an issue if there were scientifically based doubts about climate change. It would mean questioning the unequivocal results of decades of climate science. Also, Governments agree that climate science is settled. [B. C. Glavovic et al., 2021]

Is it time to take a stand?

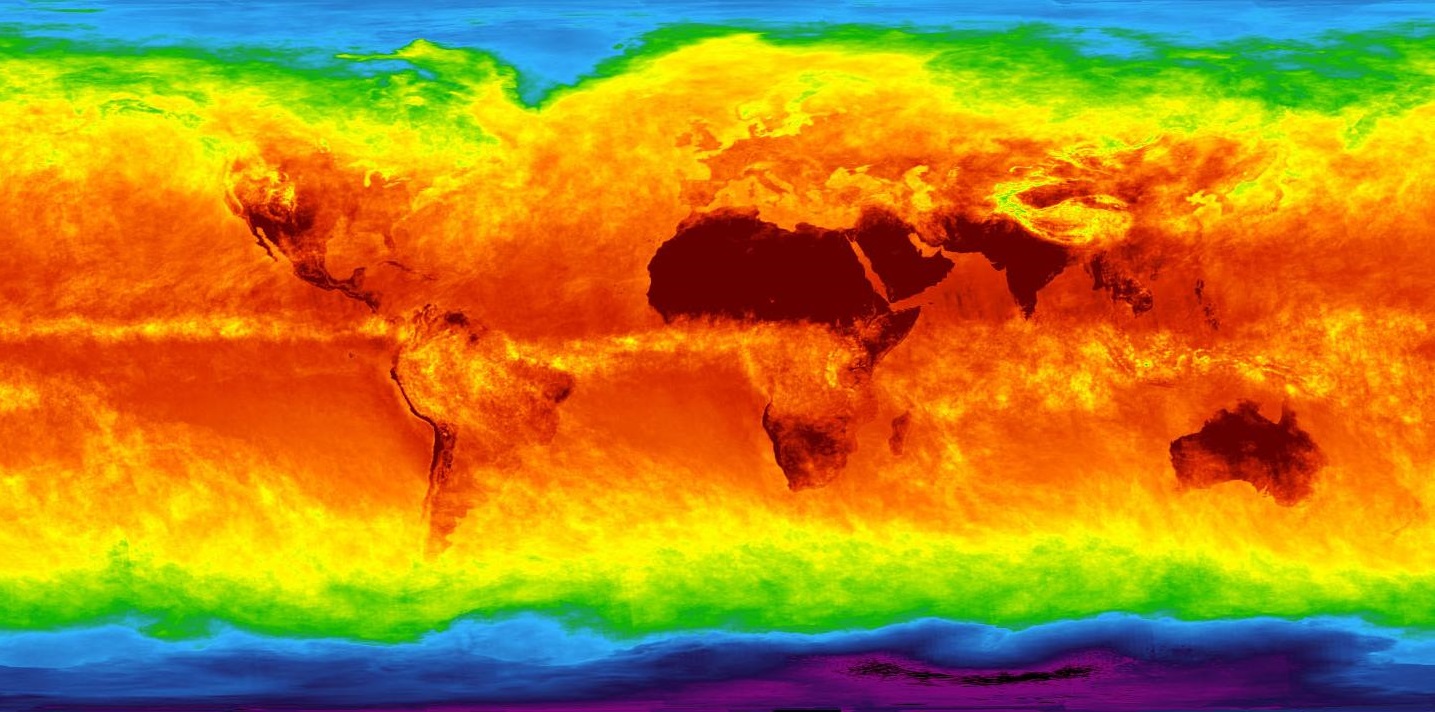

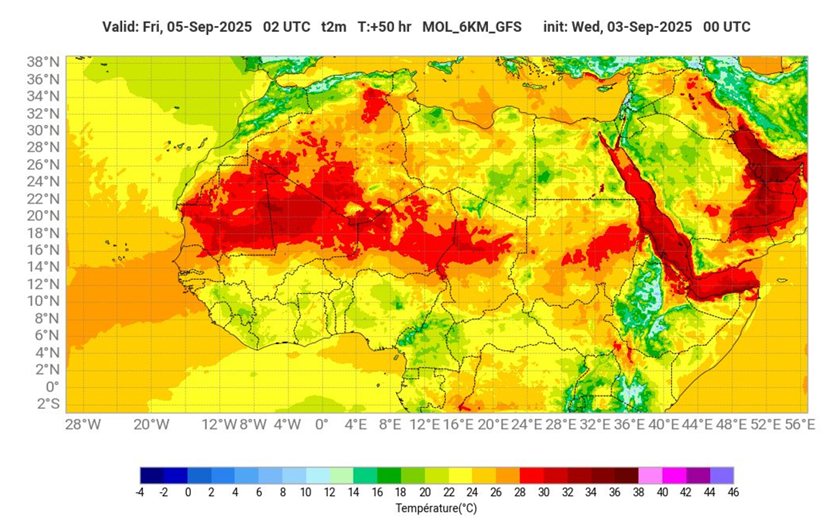

Taking a stand in the face of the climate and environmental crisis means there are no doubts about the state of risk of our planet, and about the fact that the human footprint is increasing its pressure on ecosystems and natural resources. We are experiencing climate emergencies that require urgent actions.

Taking a stand also involves defining a correct vocabulary. Climate change is a well-worn term that could remind the idea the climate has always changed [Morton, 2018], without taking into account the anthropogenic (man-made) nature of climate change. That is why The Guardian’s mission statement emphasises the need for a new vocabulary for the environmental crisis. Because talking about climate change is not the same as talking about climate crisis or global warming.

Then the questions are: Can we still avoid taking a stand? Can we talk about neutrality instead of helping to save the planet? Some scientists choose activism, abandoning the posture of “pure scientists”, disconnected from society and the world of values, interests and politics [Brüggemann et al., 2020]. And journalism? The Guardian’s experience demonstrates that abandoning neutrality and taking a stand can make a difference in supporting the creation of a solid climate culture. The hope is that such an experience will be seminal for other news and media companies.